By: Tess Redman, independent research student (sophomore)

What if someone told you that the next time you went to the doctor’s for a routine checkup, you would be shipped off to the hospital with a diagnosis of an incurable disease? Four years ago, I would probably tell that someone that they’re crazy. Until it actually happened. My name is Tess Redman. I am a sophomore/rising-junior here at River Hill. I have Type 1 Diabetes, or T1D.

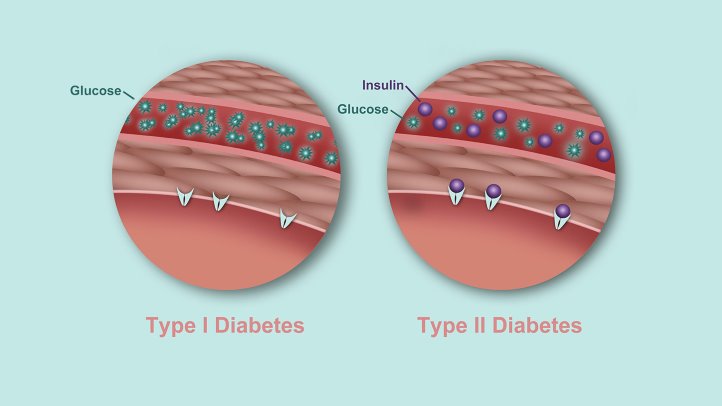

Type 1 Diabetes is incurable. Unlike Type 2 Diabetes, T1D cannot be treated with diet and exercise. It is a genetic disease that manifests, often without substantial warning, during childhood. It can certainly complicate an already complicated high school experience. Which is why I joined Independent Research, a class where I could investigate a cure for Type 1 Diabetes.

This is what I discovered.

Islet transplantation is a procedure that moves islet cells from a non-diabetic patient to a diabetic patient. These islet cells consist of a variety of other cells, including beta cells, which produce insulin, a hormone the body uses to let sugar into the cells from the bloodstream. Without sufficient insulin, the bloodstream will become clogged with sugar, and the cells that burn sugar for their daily activities will suffer (a.k.a. hyperglycemia.) Symptoms of hyperglycemia include excessive thirst, depletion of energy, and frequent urination. Normally, a diabetic will control the sugar in her blood by insulin injections; however, these injections are both costly and inconvenient for the patient. Through my research, I have identified islet transplantation as a potential cure – with one fatal flaw: a major shortage of islet donors. Because of this shortage, the ratio of transplants performed and the patients still waiting is way too high in favor of the former. Thankfully, my research has identified stem cells and xenotransplantation as the two best solutions to the islet donor shortage. By either transforming stem cells into beta cells, then transplanting them, or transplanting porcine islets (originating in pigs), the islet donor shortage will no longer stand in the way of making islet transplantation a cure for Type 1 Diabetes.

Research on both stem cells and xenotransplantation has identified similar challenges. For example, both solutions are vulnerable to immune rejection – when immune cells attack foreign cells. Immune rejection can be mitigated with immunosuppressive medications. Unfortunately, one standard regimen of medicine has not been identified, mostly because each person’s immune system is unique. Fortunately, scientists have developed other plausible methods of protecting stem cells or porcine islets from immune rejection. Encapsulation is one promising method; the cells are wrapped in a bag-like structure that is only permeable to oxygen and nutrients. Stem cells as well as porcine islets can also be genetically modified. Genetically modified stem cells have increased stress resistance and durability, while genetically modifying porcine islets deletes specific genes that are harmful to humans. This research suggests that a solution to the islet donor shortage (and, in turn, a cure for Type 1 Diabetes) is on the horizon, and professionals concur that islet transplantation should be readily available within 10-15 years.

My goal for this research is to inform and inspire others with T1D. Because this research affects us the most, we are the ones who need to generate our own research or at least advocate for others who have the means. But even if you don’t live with T1D, you can still help! If you know someone – a relative, a friend – with Type 1 Diabetes, give them this article. Better yet, do research yourself! These actions could snowball resulting in a cure being delivered even sooner than 10-15 years from now. The main thing to remember is that Type 1 Diabetics deserve a cure – and whether you conduct a research study of your own or simply donate to a T1D research foundation, you can do something to ensure that a cure is not only a hope, but a guarantee.